Running biomechanics is one of those tricky areas to get any clear answers – it seems that Physios blame every injury that creeps up on you is related to ” biomechanics”. It’s often accompanied with a ” knee bone connects to the thigh bone” explanation of how it all fits together.

But to be honest, it often just sounds like a vague connection that may not be real but seems like an easy scapegoat.

So our Physio team will go through running biomechanics step by step and how a deficit in one area can impact your loading patterns and injury.

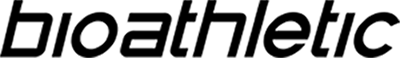

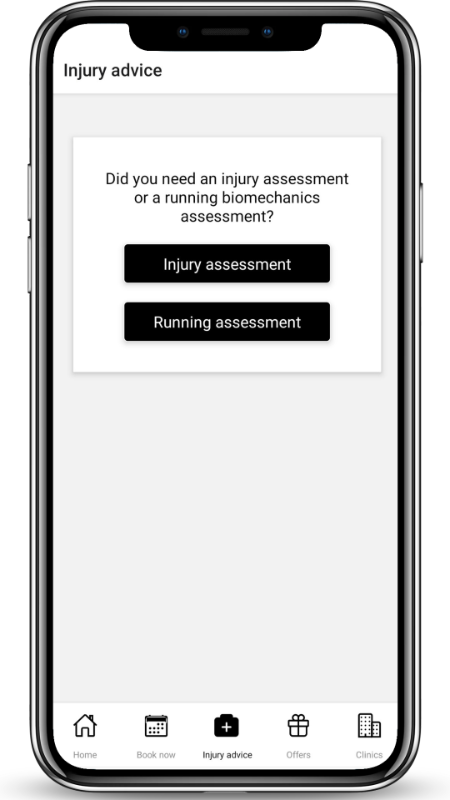

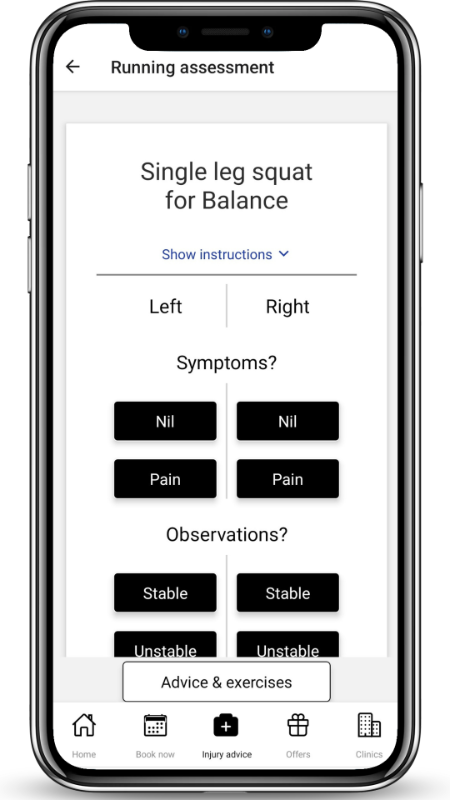

Before we get started, just a quick mention about our free biomechanical screening for runners! In our mobile app, there’s a DIY testing tool that can help identify any deficits in your biomechanics as well as provide you with a rehab program to correct most biomechanical deficits. Just download the app, go to the Injury Advice tab and click on Running Assessment.

Understanding running biomechanics

Firstly, the simplest way to think of running biomechanics is as a sequence of movements and forces that relate to each other. It’s basically a series of ” if this happens here, then that happens there” to make running a possibility.

Different components of running biomechanics

If we look at each area and what’s required (and remember, this is a very simplified version):

- Your big toe needs to bend back so you can push off your foot when it’s behind you

- Your foot and ankle needs to shock absorb when you lands, and then become rigid to give you a stable platform to push off

- Your hip needs to rotate in and out to allow the foot and ankle to move normally

- Your hip also needs to move forward and backward so the leg can swing through

- Your pelvis needs to shift around to position the leg optimally for its job at the time (the main jobs are landing and pushing off)

- The knee needs to tolerate the forces of deceleration when you’re running downhill or slowing down

- The knee also needs to buffer any difference between the ankle and hip movement (more on this later)

What it does & what it can cause

Let’s go through each of these step by step and how any changes can impact other areas

Your big toe needs to bend back

As the leg move behind you, the big toe must bend so that you can push off that foot.

If the toe doesn’t bend far enough, you can either push off with less force or lift your foot off the ground sooner.

Less push off means that the other leg is more prone to overloading as it has to work harder.

Lifting the foot earlier has the same effect (the other leg has to work harder) but it also increases how far your leg moves in front of you. That overstride then creates inefficiency and increase impact loading, which causes bone stress injuries.

Your foot and ankle needs to shock absorb

As you hit the ground, the foot and ankle move in a way that absorbs shock and reduces the spike in force on the rest of the leg.

If the foot and/or ankle don’t move well enough, you’re more at risk of injuring foot and ankle joints, connective tissues (like Plantarfascia) or creating a bone stress injury.

Your foot and ankle needs to become rigid

As you push off the ground, the foot and ankle must become more solid to give you a stable platform to push off.

If the foot and ankle aren’t stable on push off, the joints, tendons and connective tissue in the area get over stretched as the force of the leg is applied through. This can cause injuries to stabilising tendons (like Tibialis Posterior), connective tissues (like Plantarfascia) or the joints themselves (like Subtalar joint injuries).

Your hip needs to rotate in and out

As you push off and land, the hip needs to rotate to position the foot and ankle in the optimal position. (To get a feel for this, stand and push your arches down – you’ll see that the knee and hip rotate inwards).

If the hip doesn’t have sufficient rotation, it can jam the hip and cause a hip impingement. Or the rotation required gets forced through the knee and can cause knee pain.

Your hip also needs to move forward and backward

Obviously as you run, the leg swings back and forth.

If it doesn’t have enough forward movement, it can bump into the front of the joint and cause hip and groin pain.

If it doesn’t move far enough the backwards, it can cause lower back pain as the lumbar spine is forced forward by the stiff hip.

Your pelvis needs to position the leg

The pelvis is continually moving around to position the leg to either land, maintain contact with ground or push off. Pelvis movement is controlled almost exclusively by the muscles around the pelvis, so as you fatigue this movement can become compromised.

If the pelvic position isn’t right on landing, this will often cause problems like lateral hip and ITB pain.

If the pelvic position is not maintained while the leg is on the ground, this can often cause pain on the inside of the knee and ankle.

If the pelvic position isn’t stable on push-off, not only will you lose efficiency but you’re more prone to lower back pain and tendon overload.

The knee needs to tolerate deceleration

As you apply the brakes when you’re running (like running down hill or slowing down quickly), the pressure behind the knee cap increases substantially.

If the muscles can’t maintain smooth deceleration, or if the cartilage behind the kneecap is not up to the task, the result is often patellofemoral (kneecap) pain.

If the leg is not in the correct alignment as it’s decelerating (due to big toe, ankle, pelvis or hip issues), the force on the kneecap becomes concentrated in one area and causes a rapid overload.

The knee buffers any difference between the ankle and hip movement

Although the ankle in the should move in harmony, there are often small variations in those forces based on the grounds or fatigue. The knee absorbs the difference, so that it can take a little of the extra rotation caused by the hip or the ankle.

If the amounts of rotation forced on the knee is too much, or if the knee isn’t in good condition (due to cartilage where such as osteoarthritis), then it’s more susceptible to overloading and causing pain and swelling.

Fixing running biomechanics problems

This is where it gets tricky and can all go wrong.

Runners chat, a lot. So it’s common to hear a runner recommending an exercise or fix for their biomechanical issue. Sounds promising, but ends up causing more problems or doesn’t help.

Without identifying the issue, the chances of success are very low.

The best option? A full biomechanical screening from a running-specific Physio.

The second best option? Perform a biomechanical screening on yourself and identify any problems. Better still, get a free exercise program to address the issues.

In our mobile app, there’s a DIY testing tool that can help identify any deficits in your running biomechanics as well as provide you with a rehab program to correct most biomechanical deficits. Just download the app, go to the Injury Advice tab and click on Running Assessment.